There’s a joke making the rounds about a balloonist who veers off course and gets lost out in the country, and finally spots a stranger in a field.

“Can you tell me where I am?” the balloonist asks.

“You’re in a balloon 30 feet over a field,” the stranger replies.

“You must be an accountant,” the balloonist says.

“I am,” the stranger says. “How did you know?”

The balloonist explains, “Because what you told me is technically correct but totally useless.”

There are versions where the accountant gets in a snappy reply about people being snarky with those who are only trying to help them with problems they created themselves, but the core of the joke is the balloonist’s assessment of the accountant (who sometimes appears, in yet other versions, as a mathematician, or occasionally an engineer).

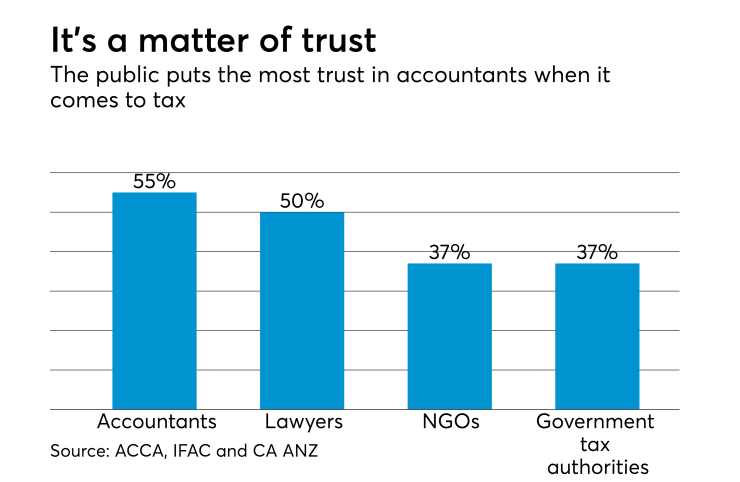

That assessment brought to mind the accounting profession’s proud boast that its members are their clients’ most trusted advisors. I don’t doubt for a moment that this is true — there are plenty of surveys that prove it — but I do wonder sometimes how much it’s worth. Let’s start with the fact that the bar is pretty low. When it comes to client trust, accountants are competing with bankers, stock brokers, insurance agents and lawyers — hardly a crowd that inspires confidence. (And that’s without bringing in politicians, the media, big business and all the other sectors of society that have seen public trust in them crater over the past 20 or 30 years.) If you can’t win “Most Trusted” there, you should probably hang up your hat.

What’s more, what do accountants get in return for all that trust? Clients question your bills, leave you out of the loop, ignore your advice, and expect you to clean up their messes. They trust you to estimate their height off the ground and to reliably identify a field when you’re standing in one, but you’ll notice that the balloonist didn’t ask the accountant for a rope, or help getting down, or advice about not getting lost in the future.

And that brings me to my main point, which is not that being the most trusted advisor isn’t worthwhile, or an admirable achievement — it is, and the accounting profession should be proud of it.

But it should only be the start.

That trust should be the foundation of a long, deep relationship, a partnership, where client confidence in their accountant meets forward-thinking advice based on business expertise, technical skills, sophisticated use of technology and data, and a constant desire to demonstrate value.

Trust and value are not synonymous, but nor are they incompatible, and a position of trust such as the one accountants already occupy is a perfect place to begin demonstrating how much more they can do. As it sees core services commoditized, the profession needs to create new services that clients want, rather than merely need, and that help them thrive, rather than merely avoid trouble. Delivering regulatory compliance is enough to engender trust, but it will not create the same perception of value as meaningful, actionable personal and business advice and proactive services.

That, then, is the challenge for the accounting profession: to stop settling for being the most trusted advisor, when they can use that as a springboard to being something else, something potentially much greater: the most valued advisor.