After having concluded the June 30, 2012, engagement and issuing an unmodified report on May 9, 2013, for a preschool organization in the City of New York, which I had been auditing for just over 10 years, I was faced with a dilemma. In the decade from July 1, 2000, to June 30, 2010, despite gross revenues hovering at $7,500,000 per year, it had accuaulated an aggregate deficit close to $900,000 — or a revenue shortfall of about a 2.5 percent — and was devolving into a financial challenge from which it might not recover.

My dilemma was this: Should I audit the ensuing year with the distinct prospect of issuing a going concern opinion, which might forestall any efforts by the organization to perpetuate, or should I work with management prospectively to develop a recovery plan?

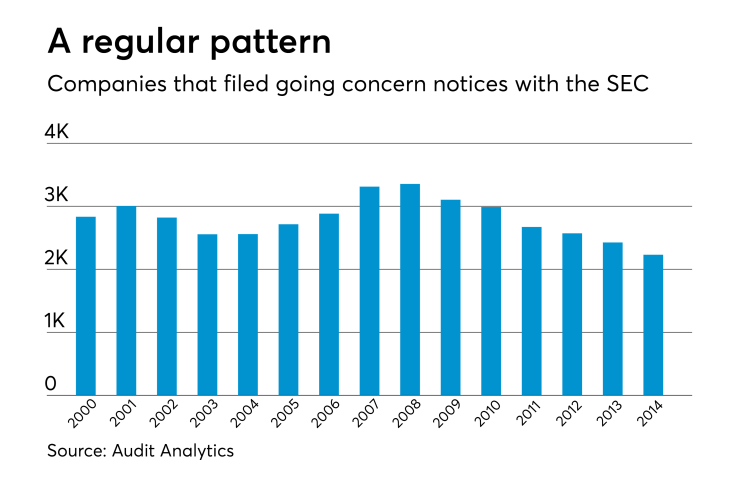

My client’s situation was not uncommon. According to data submitted by programs for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2011, New York State preschools with a similar reimbursement mechanism were under-reimbursed in excess of 3 percent. Predictably, the company was exhibiting a distinctive going concern issue. All indications were it was heading for liquidation at best or bankruptcy at worst. Not having the heart to render other than an unmodified opinion, I mentioned to the controller that if there was no improvement in the year ending June 30, 2013, I would need to issue a going concern opinion, and advised the chief executive officer to seek a new auditor for the upcoming year, while I would assist the organization in a consulting capacity, which would include the preparation of account schedules for audit. On reviewing the preliminary financials for the year ending June 30, 2013, the new auditors, as I had suspected, immediately declared that a going-concern opinion would probably be required.

By June 30, 2013, the company had a negative working capital close to $1 million in spite of its sole shareholder already having loaned the company $850,000 from personal loans and liquidated pensions & 401(k) accounts. Ongoing cash flow shortfalls were accommodated, as is often the case, with unremitted payroll taxes. Predictably, unpaid payroll taxes began to escalate while the shareholder contributed an additional $125,000 to the organization. However, working capital improved to 1 to 1 owing to the fortuitous receipt of delayed tuition payments and reclassification of unpaid payroll taxes “not” expected to be paid currently.

In December 2013, the administrators and I met with staff at the State Education Department in Albany to discuss the deepening debt inasmuch as the financial strain was becoming palpable.

By December 2014, given operations without appropriate tuition-rate increases, with no significant reduction in payroll costs, and with the imminent prospect of back-tax outlays demanded by both the IRS and New York State Tax Department, I suggested the client consider discontinuing operations.

The new auditors of the organization issued going concern opinions in the initial year and for the two subsequent years. Their opinion included an emphasis of matter paragraph within which they identified what the organization represented as a plan to emerge from its dire financial condition through positive adjustment to the prior-year’s tuition revenue (rates).

At a meeting again in May 2016, with the New York State Education Department showing deepening concern, the company was asked for a viability plan, which was provided by July. Unfortunately, none of what was proposed would enable it to continue to operate.

Now just one year since its appeal to New York State and foreseeing no relief from all deficient payroll taxes, interest and penalties, and without any imminent solution, the organization closed and initiated an assignment for the benefit of creditors with what little liquid assets remained.

Had I remained its auditor, could I have rendered even a going concern opinion while not believing the organization would emerge from its financial doldrums? Professional guidance seems to specify that a viable plan to garner added revenue or provide even further capitalization should exist, but when the organization began its financial down-spiral, such a plan simply didn’t exist. It nonetheless continued to operate for a few more years. Would an opinion more deleterious (i.e., adverse) have deprived management and ownership of the gallant attempt they made to perpetuate the organization – or simply spared them what was ultimately a fruitless effort?

I believe the profession was ill-directed in requiring a firm to opine on the continuity of a business. Financial statements by their nature, oftentimes to our chagrin, are historical. It is why dating is definitive if not precise. Even footnotes about current realizable values and known future conditions are largely factual and quantifiable and are intended to enhance rote numerical presentation. Conjecture about the future will only expose the professional accountant to unwarranted litigation by aggrieved users who have moderated their own responsibility to contemplate the information being presented. Users alone should be responsible to surmise the implications of the financials.