New Code Section 199A, which lays out the rules for when taxpayers may exclude up to 20 percent of their pass-through trade or business income, will be a challenge for accountants to explain to their clients. It could also be a challenge for accountants to analyze its implications for their own business.

And if they don’t meet the requirements to qualify for the deduction, they may want to re-examine their entity choice.

Accounting is among a select group of “specified service businesses” that, if not a C corporation, are subject to a phaseout and a W-2 limit for the Section 199A deduction. In addition to accounting, specified service businesses include actuarial science, health, law, the performing arts, consulting, athletics, financial services, brokerage services, or any trade or business where the principal asset of such trade or business is the reputation or skill of one or more of its employees or owners.

New Code Section 199A is one of the more complex provisions in the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The new section, in effect from 2018 to 2025, creates a deduction under which a non-C corporation business owner can deduct against taxable income, subject to a limitation and a phaseout, an amount equal to the lesser of 20 percent of “combined qualified business income” (determined by distributive shares excluding owner wages or guaranteed payments in the case of a flow-through entity) or 20 percent of tentative taxable income less net capital gain.

During a webinar hosted by Accounting Today, David De Jong, CPA, Esq., a partner at Rockville, Md.-based Stein Sperling Bennett De Jong Driscoll PC, described the steps necessary to compute the deduction:

- Step 1: Determine the taxpayer’s taxable income, ignoring this deduction and any capital gains losses. Compute 20 percent of this number.

- Step 2: Determine the taxpayer’s business income, totaling their income net of losses from wholly owned and flow-through businesses and applying any combined qualifying business loss that has been carried forward. Ignore capital gains/losses, dividends and nonbusiness interest. Compute 20 percent of this number.

If their taxable income, ignoring this deduction, is less than $315,000 on a joint return or $157,000 otherwise, their deduction is the lesser of Step 1 or 2. These numbers are indexed in 2019 and succeeding years for the cost of living.

If the taxpayer’s taxable income, ignoring this deduction, is more than $415,000 on a joint tax return or $207,500 otherwise, the computation under Step 2 is limited by the greater of:

- 50 percent of W-2 wages; or,

- 25 percent of W-2 wages plus 2.5 percent of the original basis of qualified property.

For a flow-through entity, the total of W-2 wages paid before elective deferrals and the original basis of qualified property will be provided pro rata to the K-1 recipients (unless affected by a special allocation in the case of a partnership).

Wages will be excluded unless properly included in a return timely filed with the Social Security Administration, including extensions, or within 60 days thereafter.

Qualified property is depreciable property placed in service within the previous 10 years or within any longer recovery period.

If the taxpayer’s taxable income ignoring this deduction is between $315,000 and $415,000 on a joint return or between $157,500 and $207,500 otherwise, in each case as adjusted for the cost of living, a pro rata portion of Step 2 will apply the limitation and a pro rata portion will not.

‘SHARPEN YOUR PENCIL’

Although tax preparation software will do some of the complicated calculations, now is the time to prepare your clients — and your accounting business, if applicable, according to Ruth Wimer, CPA, Esq., a partner in the Washington, D.C., office of law firm Winston & Strawn LLP.

“Code Section 199A will keep accountants busy,” she observed. “Individual taxpayers will have to decide what trade or business they are in, and decide if it is a specified service or not. If they happen to have more than one trade or business, they have to sort out the accounts for each and separate the payroll wages for each. A single LLC might operate multiple trades or businesses, so you will have to sharpen your pencil and figure what is the income from each trade or business that is eligible.”

“There is a huge divide between specified services and non-specified services, and then there’s also the distinction of who even has a trade or business, since only a trade or business can get the deduction,” Wimer said. She noted that “trade or business” is not precisely defined by Section 199A, and that for higher-income taxpayers, W-2 wages paid both to themselves and to others are a key factor in obtaining the 20 percent deduction.

“The new deduction encourages entrepreneurship,” Wimer noted. “For example, accountants, attorneys and journalists working as independent contractors or through their own LLC have qualified business income, whereas employees do not. And it encourages those who are not yet making a lot of money. Once they get over a maximum threshold for specified services, there’s no deduction at all.”

“It’s easy for lower-income individuals to obtain the 20 percent deduction for qualified business income,” she observed. “Individuals with total income less than $157,500 for single filers and $315,000 for joint filers can deduct 20 percent of qualified business income even if from a ‘specified service’ and also without regard to the amount of employee payroll or depreciable assets. It is only higher-income taxpayers that receive no deduction or that are subject to the Form W-2 limits.”

“The complexity starts for individuals with over $157,500 to $207,500 [single] and $315,000 to $415,000 income [joint],” Wimer explained. “In that range, specified-service income gets phased out to zero but at the same time is also subject increasingly to the Form W-2 limits until no further deduction is available. ‘Other than specified services’ just gradually becomes subject to the Form W-2 limits. The Form W-2 limit is the greater of 50 percent of wages or 25 percent of wages plus 2.5 percent of the unadjusted bases of depreciable tangible property used in the trade or business.”

For higher-income taxpayers, the new law encourages hiring employees, Wimer observed. “This is because the higher the payroll of the trade or business, the higher the permitted deduction,” she said. “Trades or businesses with depreciable assets used in the business have an alternative to using just Form W-2 wages.”

But the special definition of Form W-2 wages is not included on Form W-2 at all, Wimer indicated. “Although not an insurmountable task, the proper number to use for Form W-2 wages must be gleaned from the payroll records and isolated as directly related to the particular trade or business,” she said. “The definition of Form W-2 wages is generally that used for withholding purposes, with the addition of employee qualified plan deferrals.”

“However, the ‘specified service’ deduction is completely gone once the taxpayer is over $207,500 (single) and $415,000 (joint),” she said. “Non-specified services can retain the 20 percent deduction indefinitely, subject to the Form W-2 wage limitation.”

Wimer observed that there has been much angst over the determination of “specified services” by high-income taxpayers, noting that it’s not important to lower-income taxpayers because, for them, the 20 percent deduction applies regardless of the characterization as a specified service.

“Higher-income taxpayers are put in the ironic position of stating that neither the skills nor the reputation of employees is the principal asset of the trade or business,” Wimer said.

TOUGH DECISIONS

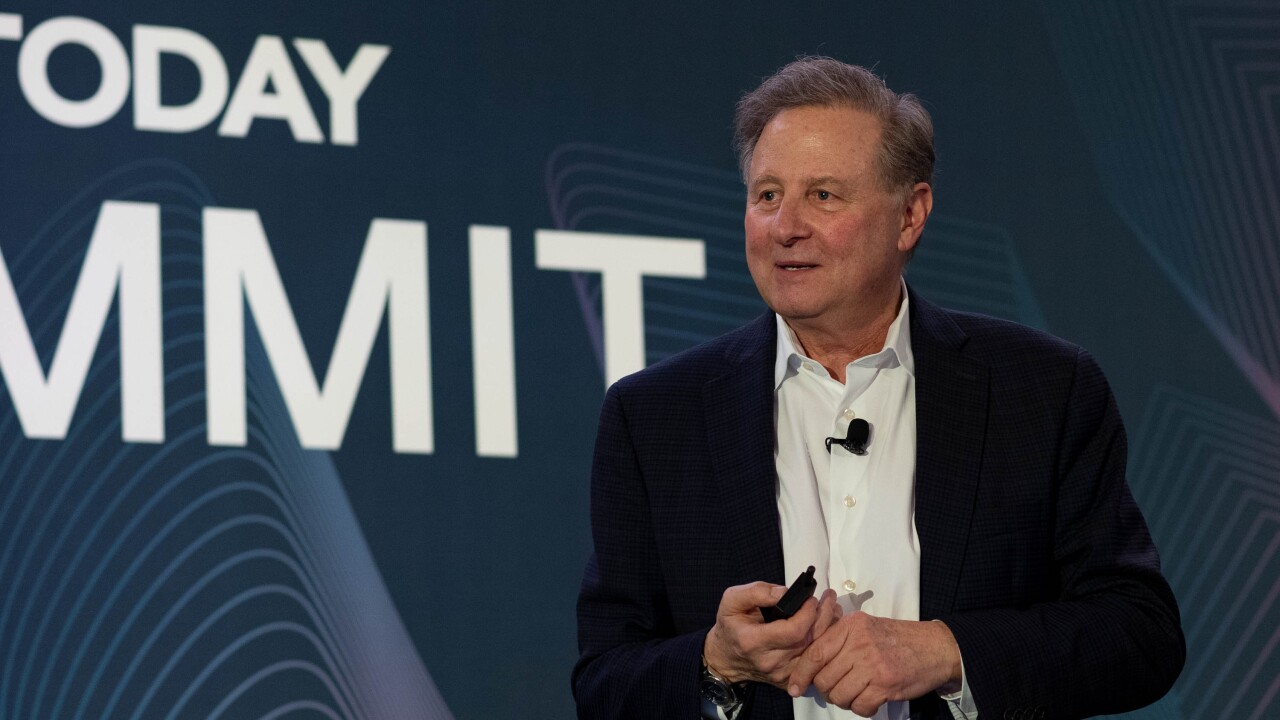

Most of the complaints about the new provision come from those making well over the limits, according to Roger Harris, president of Padgett Business Services.

“Now they are trying to decide if they should change to a personal service corporation and take advantage of the 21 percent corporate rate,” Harris said. “Every situation is going to be different. There may be a short-term benefit but long-term pain in terms of eventually selling your interest and potentially facing double taxation.”

“For example,” Harris continued, “if you leave it in the personal service corporation, it will be taxed at 21 percent, while if it flows through to you as a partner or S corporation shareholder, you will conceivably be taxed at 37 percent, so you gain the 16 percent rate differential in that first year. But what happens when you take it out in the form of dividends or a sale of your interest? And you don’t know what might have changed in the law by the time down the road when you make those decisions.”

Tom Wheelwright, founder and CEO of ProVision, agreed.

“Most accountants that are in a flow-through entity should probably continue that way,” Wheelwright said. “I don’t know any accounting professionals that leave money in the business, and if you’re going to take money out, it doesn’t make sense to be a C corporation,” he said. “Where being a C corporation does make sense is if you’re going to reinvest a large portion of the profits back into the business. Because of the double tax related to C corporations [the corporate tax plus the tax on dividends], most pass-throughs will want to continue to be pass-through entities.”