While the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act made some changes to the charitable giving provisions in the Tax Code, the climate for giving to private foundations is as strong or stronger than it has ever been, according to Jeffrey Haskell at Foundation Source.

Haskell, who heads a team of accountants and attorneys providing services to private foundations, noted that there had been talk during the long tax reform process of flattening the foundation excise tax rate.

“Under the current regime, the full tax rate is 2 percent,” he explained. “Under certain conditions that rate is cut in half, to 1 percent. It’s cut when the foundation makes grants to a certain level, as a reward. There was a proposal to simplify this by having a flat rate of 1.4 percent, but that didn’t make it into the final bill. And the other thing that might have impacted private foundations was a narrow exception to the excess business holdings rule, which generally puts a limit on the stake that a foundation and insiders collectively have in a business enterprise. That would have relaxed the rules, but it didn’t happen either.”

The fact that the final bill contained no negative targeting of private foundations was reassuring to his private foundation clients, according to Haskell. And in a positive move, the TCJA increases the adjusted gross income limit on cash contributions to public charities from 50 percent to 60 percent.

“To the extent that an exempt organization or charity pays more than a million dollars in compensation to one individual, there will be an excise tax, but this generally applies to only the biggest charities like hospitals and universities,” he said. “None of our private foundation clients – which number over 1,400 – pay compensation anywhere near those levels.”

A private foundation is a Section 501(c)(3) organization other than a public charity. It typically manages its own investments, which are normally funded by an initial donation from an individual or business.

“High-income individuals who tend to fund private foundations with significant donations are probably not itemizing their deductions,” noted Haskell. “But when they contribute, they will itemize. The tax rate is still high for high-income people at 37 percent. And the charitable deduction has not been impaired or limited in any way. There were past proposals that would have capped the charitable deduction, but they were never enacted. And the Pease limitation, which had the potential to erode up to 80 percent of itemized deductions [by reducing their value as the taxpayer’s income rose], has been repealed. So the climate for making donations is stronger than ever.”

To be sure, people are motivated by non-tax considerations, Haskell noted. “In many cases, a family has a commitment to their local community to build a park or a skating rink or a food pantry. Those people won’t care, at the end of the day, about the tax ramifications. They have a commitment to society and want to set an example for their children.”

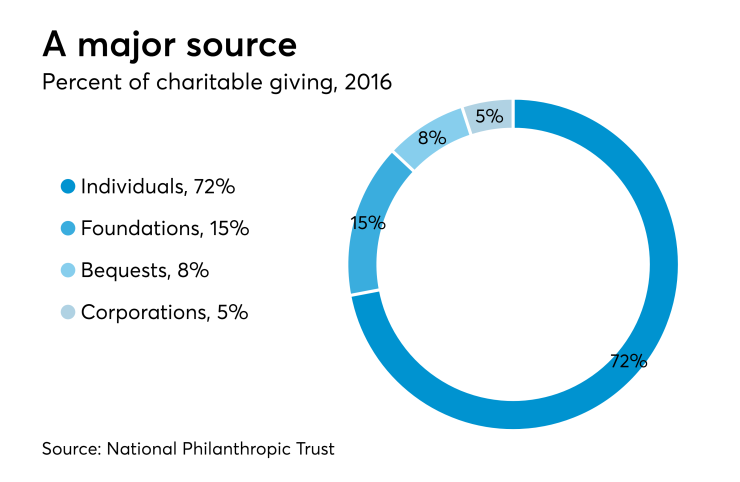

Large public charities are typically supported by private foundations, Haskell noted. “To the extent that they are hurting because of a downturn in donations from the public, private foundations can step up and fill that gap,” he said. “The need for private foundations is stronger than ever to make up any shortfall that public charities experience in receiving donations. Private foundations are committed to supporting charities in their community or regions, or in their area of interest.”

“Moreover, some corporations are seeing the lowering of the corporate tax rate as a possible opportunity to give back more to their community,” Haskell said. “There are lush years and lean years, and charities expect to receive more support from corporations in lush years. The lowering of the corporate tax rate will make for more lush years, and generate a more favorable climate for charitable giving by corporations.”