In principle, corporate directors and executives, who naturally have privileged information about their companies, aren’t supposed to use it to enrich themselves at the investing public’s expense. Yet there remain many ways in which they can nonetheless do so.

In seemingly obscure accounting

At issue is the timing of stock-option grants, a form of compensation that allows executives to purchase shares at a predetermined price. They’re typically intended as an incentive to focus on shareholder value: If the share price goes to $10, an option to buy at $1 becomes worth a lot. Sometimes, though, the grants occur suspiciously close to the announcement of positive news that causes a company’s stock to jump, providing executives with an immediate windfall — arguably at the expense of regular investors who couldn’t have known the news was coming.

Such “spring-loaded” options have long been a legal gray area. In 2002, officials cracked down on the more egregious practice of

Eastman Kodak offers a notable example. In mid-2020, just before the company’s stock price

Kodak is far from alone. Back in 2009, I

There have been dozens of other publicly reported examples over the years, and they’re probably just the tip of the iceberg. Companies don’t flag options granted near important news events, so finding them all would be a monumental and quixotic undertaking. There’s also room for interpretation: Sudden, one-off grants, for example, should raise more questions than regularly scheduled ones.

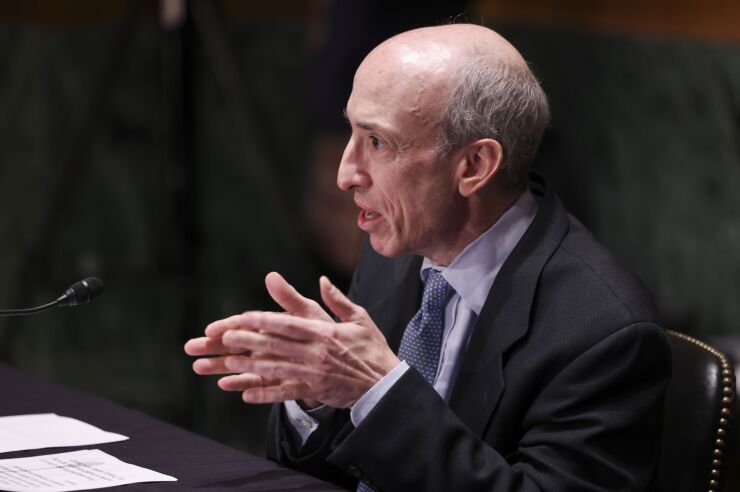

It’s thus encouraging that the SEC under new Chair Gary Gensler is subjecting the practice to greater scrutiny. In its guidance, the first of its kind in two years, the agency clarifies that companies must take any material non-public information into account when setting the exercise price and determining the value of options grants — and in their public disclosure of such grants. The guidance doesn’t change the rules, but it puts companies on notice that the SEC will no longer turn a blind eye to spring-loaded grants, as it has done for a long time.

This, in turn, suggests that the SEC is getting serious about closing gaps in its insider-trading enforcement, and might soon make examples of some companies that have pushed the limits, thinking that officials weren’t paying attention. If so, the tougher approach is welcome and long overdue.