When Sanjay Shah lost his job during the financial crisis more than a decade ago, he was one of thousands of mid-level traders suddenly out of work.

Shah didn’t take long to get back into the game, setting up his own fund targeting gaps in dividend-tax laws. Within a few years, he charted a spectacular rise from trading-floor obscurity to amassing as much as $700 million and a property portfolio that stretched from Regent’s Park in his native London to Dubai. He commanded a 62-foot yacht and booked Drake, Elton John and Jennifer Lopez to play for an autism charity he’d founded.

Fueling his ascent were what he maintains were legal, if ultimately controversial, Cum-Ex trades. Transactions like these exploited legal loopholes across Europe, allowing traders to repeatedly reap dividend tax refunds on a single holding of stock. The deals proved hugely lucrative for those involved — except, of course, for the governments that paid up billions. German lawmakers have called it the greatest tax heist in history.

Denmark, which is trying to recoup some 12.7 billion krone ($2 billion), or close to 1 percent of its gross domestic product, says the entire enterprise was a charade. Its lawyers are seeking to gain access to bank records that they maintain will prove that point. Authorities have now frozen much of Shah’s fortune and he’s fighting lawsuits and criminal probes in several countries. His lawyers have told him he’ll be arrested if he leaves the Gulf city for Europe, though he’s yet to be charged.

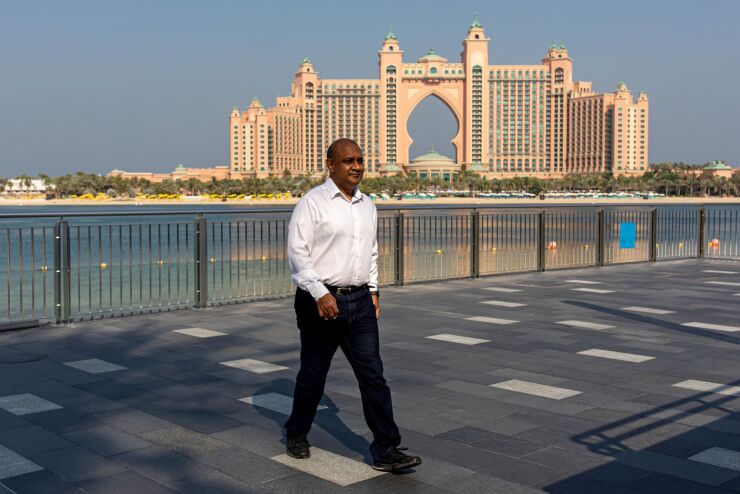

But in a series of recent interviews from his $4.5 million home in Dubai, Shah was unrepentant.

“Bankers don’t have morals,” the 50-year-old said on a video call. “Hedge-fund managers, and so on, they don’t have morals. I made the money legally.”

‘Allowed it’

Shah and the firm he set up — Solo Capital Partners LLP — are central figures in the Danish Cum-Ex scandal, in which he said his company helped investors to rapidly sell shares and claim multiple refunds on dividend taxes.

Authorities have been probing hundreds of bankers, traders and lawyers in several countries as they try to account for the billions of euros in taxpayer funds that they say were reaped. But Shah says he’s being made a “scapegoat” for figuring out how to legally profit from obscure tax-code loopholes that allowed Cum-Ex trades, named for the Latin term for “With-Without.”

“Prove that any law was broken,” Shah said. “Prove that there was fraud. The legal system allowed it.”

The Danish tax agency, Skat, says it’s frozen as much as 3.5 billion Danish kroner of Shah’s assets, including a $20 million London mansion, as part of a sprawling lawsuit against the former banker and his alleged associates.

The agency hasn’t seen “evidence that supports that real shares were involved in the trades relating to the dividend refunds reclaimed in the Shah universe,” it said in a statement. “It looks like paper transactions with no connection to any real holding of shares.”

Shah still reaps about 200,000 pounds ($250,000) a year from renting out his properties, he said, less than half of what he got before the arrival of COVID-19.

The former trader faces additional heat in Germany, where prosecutors are probing him as part of a nationwide dragnet that’s targeted hundreds of suspects throughout the finance industry.

Feeling robbed

In Denmark, the case against Shah has triggered public anger. The country, which is in the middle of an economic recession wrought by the coronavirus, claims it has been robbed.

“In a country like Denmark, and mainly in the times of COVID-19, it is of substantial importance,” said Alexandra Andhov, a law professor at the University of Copenhagen. The nation’s tax authorities have dealt with alleged fraud cases before but “not in the amount of $2 billion,” she said.

Shah appeared at ease and upbeat while outlining how he’d be arrested if he tried to fly home to London. Married with three children and based in Dubai since 2009, Shah has spent the past five years engrossed in legal papers and talking to his lawyers, he said. To the authorities trying to extract him from his exile, he has a piece of advice: know your Tax Code.

“It’s very nice to put somebody’s face on a front page of a newspaper and say, ‘Look at this guy living in Dubai, sitting on the beach every day sipping a Pina Colada while you’re broke and you don’t have a job’,” he said. “I would say look at your legal system.”

First strides

Shah is hardly the only person ensnared in the European Cum-Ex scandal. German prosecutors have been more aggressive than their Danish counterparts and have already charged more than 20 people. At a landmark trial earlier this year, two ex-UniCredit SpA traders were convicted of aggravated tax evasion.

One of them, Martin Shields, told the Bonn court that while he had made millions from Cum-Ex, he now regretted his actions.

“Knowing what I now know, I would not have involved myself in the Cum-Ex industry,” said Shields, who avoided jail time because he cooperated with the investigation.

A decade ago, Cum-Ex deals were wildly popular throughout the financial industry. Shah says he picked up the idea during his years as a trader in London for some of the world’s biggest banks.

The son of a surgeon, Shah dropped out of medical school in the 1990s and moved into finance. He first observed traders exploiting dividend taxes while at Credit Suisse Group AG in the early 2000s, a strategy known as dividend arbitrage. Will Bowen, a spokesman for the Swiss bank in London, said “the lawsuits referred to relate to a period after Sanjay Shah worked at Credit Suisse.”

Shah didn’t fully embrace Cum-Ex until he was hired by Amsterdam-based Rabobank Group several years later as the financial crisis was beginning to rip through the industry. Rishi Sethi, a spokesman for Rabobank, declined to comment on former employees.

Big ambitions

After being laid off, Shah says he received offers from several brokerage firms that included profit-sharing. But that wasn’t enough for him, so he set up his own firm.

“I don’t want to make a share,” he said. “I want to make the whole lot.”

That ambition was memorialized in the name that Shah picked for his company: Solo Capital Partners.

Shah said he had about half a million pounds when he started Solo. Within half a decade, his net worth would soar to many multiples of that. According to his recollection, JPMorgan Chase & Co. also played a pivotal role in helping him get started because they were the firm’s first custodian bank. Patrick Burton, a spokesman for the New York-based bank, declined to comment.

The scheme that Shah allegedly orchestrated was audacious. A small group of agents in the U.K. wrote to Skat between 2012 and 2015, claiming to represent hundreds of overseas entities — including small U.S. pension funds along with firms in Malaysia and Luxembourg — that had received dividends from Danish stocks and were entitled to tax refunds. Satisfied with the proof they received, the Danes say they handed over some $2 billion.

Luxury homes

But most of the money, authorities say, flowed instead directly into Shah’s pockets. The agents and the hundreds of overseas entities had merely been part of an elaborate web he’d created along with a series of dizzying “sham transactions” set up to generate illicit refund requests, according to the country’s claim in U.K. courts.

Starting in January 2014, more than $700 million allegedly landed in Shah’s accounts. He funneled his wealth into property across London, Hong Kong, Dubai and Tokyo, Shah said, amassing a portfolio that he put at about 70 million pounds. He bought a 36-foot yacht for $500,000 in 2014 and called it Solo before upgrading to a $2 million, 62-ft model, the Solo II.

Shah’s lawyers said in his latest filing in the London lawsuit last month that Solo — which went into administration in 2016 — provided “clearing services for clients to engage in lawful and legitimate trading strategies that were conducted at all times in accordance with Danish law.”

They said that dividend arbitrage trading is a widely known and “wholly legitimate trading strategy.” Shah’s lawyers are also contesting whether Denmark has jurisdiction to pursue its claim in the English courts.

It’s been five years since Shah learned he was facing a criminal probe, when the U.K. National Crime Agency raided Solo’s offices following a tip to British tax authorities from the company’s compliance officer.

Slightly bored

His lawyer at the time, Geoffrey Cox, told him in 2015 that he had nothing to fear and that it would all be over soon, Shah said. Cox, who would go on to become U.K. Attorney General and play a pivotal role during various Brexit crises last year, declined to comment.

But instead Shah’s legal problems are just beginning. A mammoth three-part civil trial covering Skat’s allegations against Shah will start in London next year. The accusations are also at the heart of a massive U.S. civil case targeting other participants in the alleged scam.

Criminal probes in Germany and Denmark are still rumbling on. While Shah said he hasn’t been contacted by the U.K. Financial Conduct Authority, the watchdog said in February that it’s investigating “substantial and suspected abusive share trading in London’s markets” tied to Cum-Ex schemes. A Dubai court threw out Denmark’s lawsuit against Shah in August, though it is appealing the decision.

Back in Dubai, Shah said the ongoing saga is starting to wear him down.

”It’s been quite nice spending time with the kids and family but now where I am, I’m just getting bored and fed up,” Shah said. “It’s been five years. I don’t know how long it will take for matters to conclude.”

— With assistance from Frances Schwartzkopff