Governor Phil Murphy’s progressive agenda, outlined in his first New Jersey budget, depends on approval of $1.5 billion in new riches from Democratic lawmakers reluctant to increase residents’ financial burden in one of the highest-taxed U.S. states.

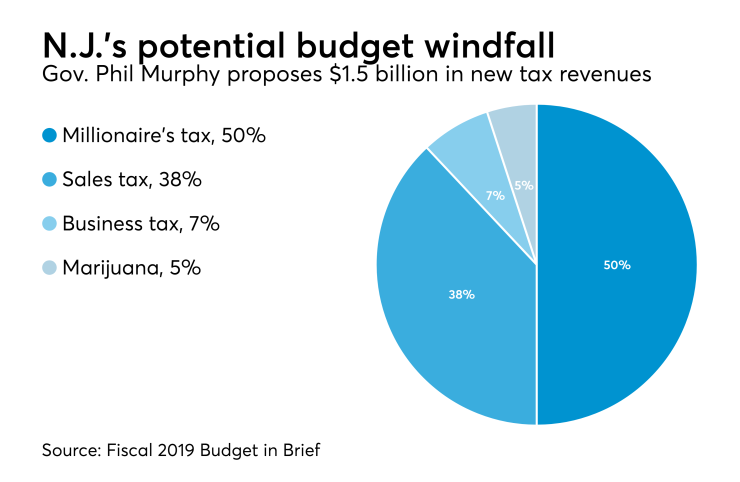

A newcomer to elective office, Murphy has proposed a record $37.4 billion spending plan that presumes lawmakers will approve new taxes on millionaires, retail sales, legalized marijuana, electronic cigarettes, corporations and such services as Uber and Airbnb. That’s the greatest revenue risk for a budget since 2009, the last time a governor tried to tap New Jerseyans for more than $1 billion in general-fund tax increases.

If Murphy’s fellow Democrats who control the legislature don’t cooperate, they’ll potentially derail a record $3.2 billion pension payment and more school funding. Should they sign on, they may antagonize voters and drive wealth from a state more burdened than most by President Donald Trump’s new $10,000 limit on state and local tax deductions.

“New Jersey was very hard hit by the cap on the SALT deduction and as a result there’s a sentiment that there’s less disposable income, less wealth available to New Jersey taxpayers,” Baye Larsen, a Moody’s Investors Service senior analyst, said in an interview. “Therefore, this is a particularly difficult time to raise taxes."

Tapped Out

Cash-poor New Jersey cultivates annual budget drama, and the last episode played out nationally, with Republican Governor Chris Christie scorned for relaxing with his family on a beach that was closed to the public amid a budget impasse and government shutdown. This year, Democratic lawmakers were lukewarm after Murphy’s budget address on March 13.

After eight years of Christie, Democratic lawmakers should be natural allies with Murphy, a retired Goldman Sachs Group Inc. senior director and U.S. ambassador to Germany. With his victory in November over Christie’s lieutenant governor, Kim Guadagno, his party controls the legislative and executive branches. The path was smooth, it seemed, to Democratic goals that Christie had blocked: legalized recreational marijuana, a $15 minimum wage and turnaround for neglected mass transit.

Instead, the relationship appears to be chilly as the budget heads to its first legislative committee hearing on March 28.

Though New Jersey’s governor is the nation’s most powerful — with authority to appoint the attorney general, hand-pick appointees for heavy-spending commissions and veto budget line items — Murphy needs legislative approval for the new revenue he’s seeking.

“The budget shortfall, school funding, higher education, New Jersey Transit falling apart —we have all these problems and there’s only one way to deal with them,” former Governor Jim Florio, a Democrat ousted after one term on a tax-increase backlash, said in an interview. “It’s not a spending problem so much as a revenue problem.”

Murphy’s drive for a cannabis law within his first 100 days has been slowed by public hearings and concerns about its effect on cities from Senator Ronald Rice of Newark, chairman of the Legislative Black Caucus. On a millionaire’s tax, Murphy lost a champion in Senate President Steve Sweeney from West Deptford, sponsor of a tax on the rich that Christie vetoed five times. Sweeney last month told reporters that the measure “should be the absolute last resort” in light of the federal tax changes signed by Trump in December.

“These tax increases, particularly the millionaires tax, will feel more costly to taxpayers because federal tax law no longer permits deductions for state and local income or sales taxes, and limits the deduction for property taxes to $10,000,” Moody’s analyst Larsen wrote in a March 22 note to clients. Her firm rates New Jersey’s credit A3, four steps above junk. Only Illinois has a lower state rating.

Lesser Evil

Sweeney has his own proposal to gain $657 million via a 3 percent surcharge on corporations earning more than $1 million annually. Murphy has said it wasn’t an alternative to his millionaire’s tax, for an estimated $765 million. That won’t happen without Sweeney’s posting it for a vote in the legislature’s upper house.

“He’s going to realize there’s no stomach on the Democrat side for raising these taxes,” Assembly Minority Leader Jon Bramnick, a Republican from Westfield, said of Murphy.

Sweeney didn’t respond to two telephone calls for comment. A statement issued by him and five colleagues immediately after Murphy’s budget speech said the governor’s “ambitious proposals” had appeal, “but will require thorough review and consideration to determine if they are achievable.”

Voter Backlash

Jon Corzine, like Murphy a Goldman veteran, was the most recent governor to pitch $1 billion-plus tax increases. His first budget, in 2006, boosted the sales tax to 7 percent from 6 percent and applied it to more consumer services, to raise $1.4 billion. Democratic lawmakers resisted, resulting in a week-long government shutdown, but ultimately they approved it with an agreement that put half the money toward property-tax relief.

In 2009, Corzine again pitched tax increases in excess of $1 billion. The legislature went along with a temporary higher tax on $400,000-plus incomes and higher levies for liquor, wine and cigarettes. He was ousted that November by Christie, who promised to return New Jersey to fiscal health.

Instead, missed revenue forecasts and an unfunded pension-and-benefits liability that reached $184.3 billion in 2017 led to a record 11 downgrades of New Jersey debt by the three major credit-rating companies during Christie’s tenure.

Murphy inherited the nation’s highest property taxes, the second-lowest credit rating behind Illinois and the least-funded pension system among U.S. states. New Jersey’s fiscal health ranked the worst in a 2017 study by the Mercatus Center at George Mason University in Arlington, Virginia.

Budget Abyss

A millionaire’s tax would cover less than one-tenth of an estimated $8.7 billion budget deficit heading to July 1, the start of the fiscal year. Still, Murphy has support from Senator Richard Codey, a Democrat from Roseland elected to the upper house in 1982.

“My district is the wealthiest in the state of New Jersey,” Codey, who represents the Essex County suburbs of New York City, said in an interview. “I haven’t had one phone call to my district office complaining about that idea.”

Murphy has declined to comment on whether he has a back-up plan should his tax increases not happen. Publicly, he conveys confidence that less-enthusiastic Democrats will come around.

“There’s a long way to go,” he said during his monthly radio call-in program on March 22. “Our doors are open. Very much.”