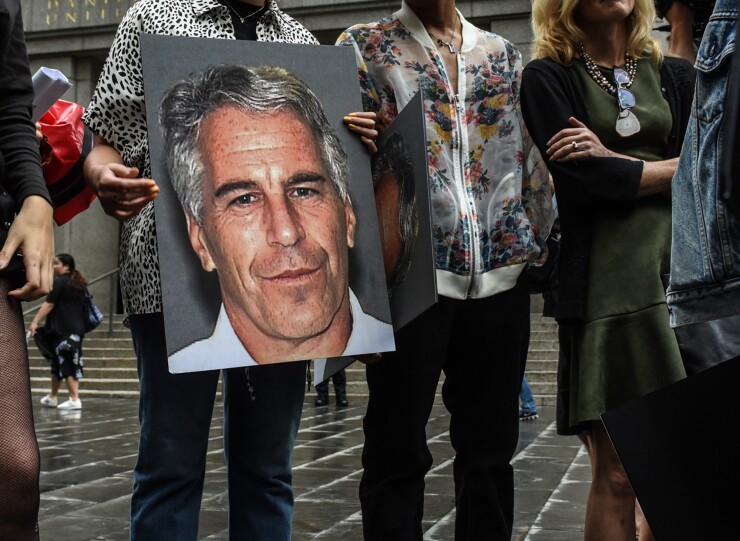

There are a lot of theories about the sources of Jeffrey Epstein’s wealth and how he earned his one-time reputation as a brilliant money manager. One thing that isn’t disputed is that he knew how to cut his tax bills by setting up shop in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

That didn’t require any particular skill on Epstein’s part. The rules set by the Economic Development Commission in St. Thomas allow some businesses in the U.S territory to, after meeting certain conditions, significantly lower their exposure to federal corporate and personal income taxes by possibly 90 percent.

The rules have tightened since Epstein made his first major investment in Virgin Islands in the late 1990s. But the question remains: Since one of his self-professed specialties was helping the ultra-rich reduce their tax income, what role did the Virgin Islands play in enriching Epstein and his clients?

Six years passed between Epstein’s buying a private island in the territory and 2004, when authorities began enforcing stricter rules on tax-break eligibility. By then Epstein was a veteran player — and perhaps wizened adviser — who has incorporated multiple dozens of businesses.

Huge Gift

Even now, what’s legally on offer there “is a huge gift” for people of means, said Tim Richards, a lawyer specializing in international tax at Richards & Partners in Miami.

The rules could allow businesses like Epstein’s to avoid paying regular U.S. taxes, for example, by counting the company’s income where its computer servers are located.

The tax systems of U.S. territories like the Virgin Islands mirror those of the mainland except that the recipient is not the U.S. Treasury but the local government. For non-U.S. income, they have the authority to reduce taxes in some cases, such as to bolster economic development.

“It’s one of the only places that U.S. citizens can actually reduce their federal income tax liability,” said William Blum, an international tax lawyer at Solomon Blum Heymann LLP, who served as counsel to a former governor of the USVI.

Epstein started benefiting around two decades back, when he moved his firm, originally called J Epstein & Co., from New York to St. Thomas. Mystery still surrounds the operations of the business, renamed Financial Trust Co., though a few investments have come to light, including $80 million invested into hedge fund DB Zwirn & Co. between 2002 and 2005.

He made another tax play in 2012, securing approval for his Southern Trust Co. to join the tax-incentive program as a designated service business, documents show. His 50-50 partnership in a local marina with New York real estate developer Andrew Farkas is also a beneficiary of the program.

Southern Trust received a 90 percent exemption on its US VI income taxes and a 100 percent exemption on gross receipts and excise taxes for a decade starting in February 2013, according to its filing with the island.

The economic development tax breaks can go even further for Virgin Islands residents, with a 90 percent reduction in personal income tax also available.

“The USVI is unique in that it has congressionally approved tax benefits found in the Internal Revenue code, but at the same time, the American flag flies, there’s a U.S. federal court, appeals go to the U.S. Third Circuit, you’re not outside the U.S. banking system and you even have a U.S. area code,” said Joseph DiRuzzo, a long-time USVI tax attorney.

“It provides all the accouterments of the U.S., with some of the tax benefits that one would typically only see offshore,” he said.

Residency Rules

It’s not clear whether Epstein — who owns a Manhattan townhouse, a Florida villa, a New Mexico ranch and an apartment in Paris in addition to two private islands off St. Thomas — was ever a USVI resident.

Typically a taxpayer must spend at least 183 days a year on the islands. Flight records provided by JetTrack suggest Epstein spent just 56 days in the region in 2017 and 13 in 2018. A former employee who spoke on the condition of anonymity said Epstein always traveled to his island via private jet.

If Epstein moved around between his properties, mostly those outside the Virgin Islands, Southern Trust was putting down roots. To secure its tax status, Epstein agreed to invest more than $400,000 in the business and to employ 10 full-time employees by the end of its sixth year of operation, 80 percent of whom had to be Virgin Island residents.

What the company does is unclear. The EDC certificate describes it as “providing an extensive DNA database and to develop a data-mining platform.”

Just a Little Sign

There’s little sign of the company’s local presence at the commercial plaza on St. Thomas, featuring a Sami’s Mini-Mart and the Happy Nails salon, where its office is registered. Its name is listed only on a dockside building directory. It doesn’t appear to have a website.

The last compliance review was completed in November, according to Kamal Latham, chief executive officer of the jurisdiction’s Economic Development Authority, and Southern Trust was found to be within the law.

The reviews are more rigorous than before 2004, when reports about abuses caused the Internal Revenue Service to clamp down on designated service businesses — typically high-income hedge funds, consultancies and investment services — that were dominating the program.

Some wealthy U.S. taxpayers, for example, were piggy-backing onto existing EDC corporations and claiming residency simply to enjoy the island’s tax benefits. A Senate Finance Committee investigation concluded some taxpayers were able to falsely claim USVI residency based only on a driver’s license or voter registration card, not time lived there.

Crackdown in 2004

The crackdown came in 2004, after the IRS began investigating businesses on the island.

“Certain promoters are advising taxpayers to take highly questionable, and in most cases, meritless positions in order to avoid U.S. taxation and claim a tax benefit under the laws of the Virgin Islands,” the IRS said in its 2004 notice that resulted in far more stringent rules.

Such changes didn’t put Epstein off the jurisdiction. As well as Southern Trust Co., he has at least a dozen other entities there, holding assets such as his planes and properties.

“It’s great for international businessmen with overseas assets,” said Richards, the lawyer. “You employ people, you have your servers there and your tax rates go down dramatically.”

— With assistance from Jonathan Levin