The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, signed into law nearly a year ago, may have rescued the corporate income tax, according to Jorge Barro and Joyce Beebe, fellows in public finance at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

The share of the corporate income tax in the federal government’s revenue has been steadily declining since the start of the postwar era, they noted.

“Immediately after World War II, the corporate income tax accounted for approximately 30 percent of the federal government’s gross receipts,” said Barro. “In the 1960s and 1970s, this ratio decreased to less than 20 percent, and the next two decades saw a further decline to 10 percent of federal revenue.”

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the ratio has been hovering around the 10 percent mark. “While some of this decline has been the result of reductions in the corporate tax rate, much of it is attributable to a declining corporate tax base,” said Beebe.

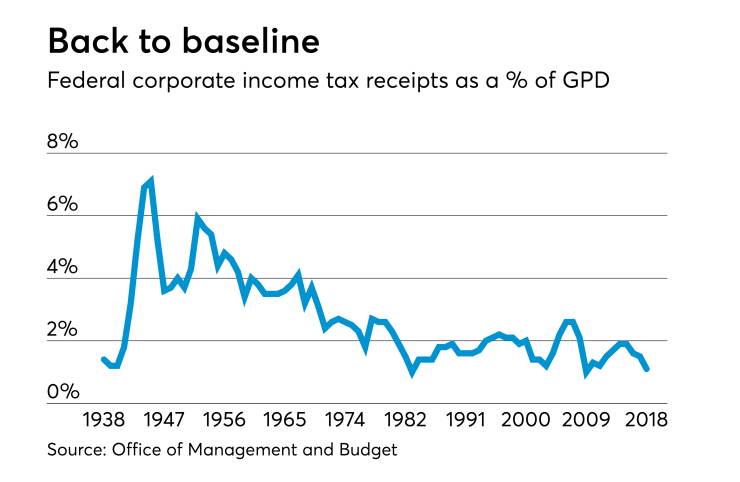

Total corporate income tax revenue as a share of gross domestic product has also trended downward over time, Barro and Beebe observed, citing the fact that although the tax rate was higher than that of other countries before tax reform ushered in the tax cuts of the TCJA, the U.S. collected a smaller share of corporate tax revenue as a percentage of gross domestic product.

The cause of this phenomenon of high-rate, low-revenue collection has been the focus of the corporate tax reform debate for decades. Academic scholars, lawmakers, and the private sector all have different perspectives on how to repair the corporate income tax, and they all have legitimate reasons to hold different perspectives, suggested Barro and Beebe.

“Although the statutory rate was high, the effective rate – taxes paid divided by profits – was on par with other developed countries,” Beebe indicated. “Because of the credits, deductions, benefits, and subsidies included in the calculation, the tax base was narrow by design and the tax burden per dollar of profit was not as high as 35 percent.”

Two significant corporate tax provisions in the TCJA expanded the tax base – the net operating loss carryover modification and limits on interest expense deduction, according to Barro and Beebe.

“The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act provided a political solution to the drawbacks of the corporate income tax,” said Barro. “The base-broadening and rate-reducing features appeal to academia, and the significant rate reduction and favorable repatriation rate appeal to industry. U.S. businesses are facing an unprecedented low-CIT environment and a business-friendly atmosphere that is certain to compete with low-tax jurisdictions.”

Barro advocates low or no corporate income tax. “I’m a proponent of more taxation on the household side and less on the corporate side,” he said. “In theory, these are taxes that could just be paid at the household level. By taxing all business income at the household level, you add a measure of progressivity to business income taxation. For example, a wealthy person or a low-income individual who both own a share of the same company would pay the same corporate tax, but if business income were taxed at the household level, the higher-income individual would pay higher marginal taxes – there is some progressivity to paying taxes on dividends. So I would be in favor of taxing all business income at the household level and potentially raising the top marginal tax rate in order to eliminate the corporate income tax. But this is not likely to happen – there are a lot of reasons why the corporate income tax is going to remain.”

“Many issues remain, such as looming deficits, still-complex compliance procedures, and the uncertain longevity of the TCJA’s corporate provisions,” he continued. “There is not a single panacea for the CIT -- what is required is to find a compromise that everyone can live with. The TCJA offers a starting point for such a compromise to revitalize the corporate income tax.”