U.S. corporations are required to pay a one-time tax on their offshore profits, but don’t expect those stockpiled funds to come onshore quickly -- or ever.

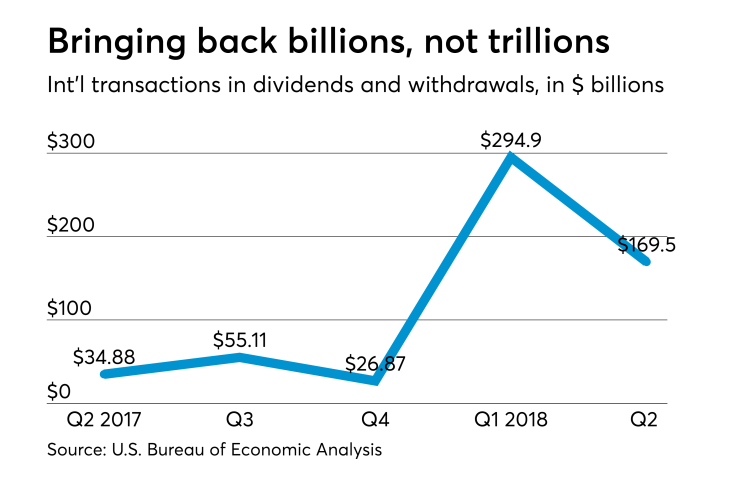

Companies repatriated $169.5 billion in the second quarter, according to data released Wednesday by the Commerce Department, up from $34.9 billion a year earlier. Still, that followed a downwardly revised $294.9 billion returned in the first quarter.

The numbers for the first half of the year are just a fraction of the more than $3 trillion companies are estimated to have accumulated overseas to defer U.S. taxes on the money. President Donald Trump has said, without specifying his source, that he expects more than $4 trillion to return to the U.S., which will help to create jobs and more investment.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the tax overhaul signed into law by Trump in December, gave companies incentives to bring money back to the U.S. by lowering the tax rate on repatriated profits. The new rules set a one-time rate of 15.5 percent on cash and 8 percent on non-cash or illiquid assets. Previously, companies had to pay the old 35 percent corporate rate, but only if they brought the money back to the U.S.

Companies pay the “deemed” tax whether or not the profits are actually brought back onshore. They can elect to pay the amount over eight years, despite when, or if, the money is brought back to the U.S.

“A lot of companies have a large liability, but they don’t have a large amount of cash sitting out there,” said Cory Perry, international tax senior manager at Top Six Firm Grant Thornton. “They have it invested in manufacturing or plants or have it in a holding company where it is deployed in other jurisdictions.”

The Commerce Department figures reflect the earnings from post-1986 through 2017 -- all subject to the repatriation levy -- as well as new profits from this year.

“We hear from the president that as soon as the $4 trillion comes it will be a chicken in every pot and America will now be great,” said Gordon Gray, the director of fiscal policy at think tank the American Action Forum. But ultimately, investment decisions are driven by the after-tax returns on the projects, rather than whether cash is sitting in a bank account in Ireland or New York, Gray said.

The Internal Revenue Service has issued guidance several times this year outlining when the repatriation tax applies and how to pay it, but those rules aren’t yet finalized. For companies with cash, it’s not necessarily that simple to bring it back, Perry said. Local laws in countries such as Brazil and China can make extracting cash difficult. And it makes sense for some companies to keep it located overseas because they hope to expand there, he said.

The Joint Committee on Taxation estimates the repatriation levy will generate $338.8 billion in tax revenue over 10 years. If cash and non-cash assets were to be repatriated in equal amounts that would equal corporations paying taxes on approximately $2.86 trillion.